Any new film by Quentin Tarantino (affectionately known as QT by his fans) is a motion picture event of the year. After all, he is part of a rare breed of top-tier filmmakers working in Hollywood who could launch any project with a single—or perhaps more accurately, a singular—premise, drawing actors who want to work with him like ants to candy (even if he often rotates from a stable of familiar names), as well as investors who like a shot at delivering both box-office success (it has already exceeded the US$100 million mark domestically) and awards prestige.

Tarantino has been tirelessly working for three long decades, but in recent years he has been stubbornly adamant that he will stop at ten. He’s already on his ninth feature, which had its world premiere at the Cannes Film Festival earlier this year, a festival that gave him one of cinema’s most coveted prizes—the Palme d’Or—for 1994’s Pulp Fiction.

Although he left empty-handed at Cannes this time round, it would be shocking if Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood is shut out from the Oscars in 2020. A shoo-in for nominations for Best Picture, Director, Leading Actor, Supporting Actor and Original Screenplay, it should also score nods in most technical categories, including Cinematography, Film Editing, Production Design, Costume Design, Sound Mixing and Editing.

In other words, this is one of the finest American pictures of the year—and I’m pretty sure Mr. Tarantino wants that Best Director Oscar badly, after already winning two separate Oscars for Original Screenplay previously.

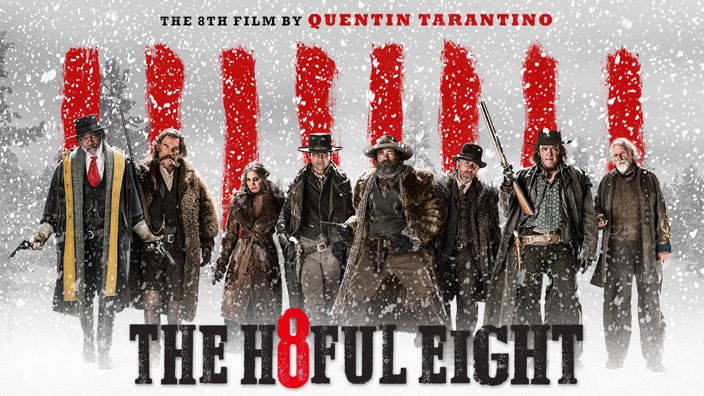

QT taking home Best Original Screenplay for Django Unchained at the 2013 Oscars. His follow-up Western was The Hateful Eight

Hollywood is incidentally also his most mature and restrained work to date—and I see this as a double-edged sword, at least in the context of mainstream moviegoing. On one hand, if you are already a die-hard fan, as I am, it is another glorious creation that sits proudly (I daresay) at the highest echelons of the QT canon, and may possibly get even better with multiple viewings.

On the other hand, moviegoers who go in ‘blind’, without any context of Tarantino’s previous works, or at least some appreciation of history as it were in 1969’s Los Angeles, particularly the tragic Charles Manson-Sharon Tate narrative, will likely find it uncharacteristically meandering and less emotionally resonant than some of his other pictures.

Bursting with cinematic and popular cultural references, both from the late 1960s and his own work, notably Inglourious Basterds (ultraviolence against Nazis!), Django Unchained (that intense dog-ripping-flesh scene!), Death Proof (male gazey overload of female feet, legs and butts… plus men and their cars!) and Kill Bill (Bruce Lee, well symbolically…), one could call Hollywood a QT greatest hits showcase—and at this juncture of his enviable career, one might not begrudge that he deserves some kind of platinum compilation album.

In fact, this ‘greatest hits’ reading of Hollywood is a good segue into its eclectic soundtrack of songs and music, capturing the aural zeitgeist of the period, including an inspired use of Bernard Hermann’s unused score for Hitchcock’s Torn Curtain (1966).

What’s most interesting is that most of these songs are employed diegetically (e.g. coming from the radio of moving cars), yet Tarantino’s carefully-calibrated sound mix gives it a reverberating, almost non-diegetic effect. There are a lot of these scenes—of cars on never-ending freeways (hey it’s Los Angeles), of songs bursting into the world or getting cut short because, well, the keys to the ignition need to be taken out at some point.

Leonardo DiCaprio is the star attraction in more ways than one, playing Rick Dalton, an emotionally vulnerable actor at the fringes of Hollywood hoping for some breakthrough, while Brad Pitt is Cliff Booth, his unassuming stunt double and good friend (plus chauffeur). Sharon Tate, a supporting but anchor figure in Tarantino’s narrative, is played by Margot Robbie.

All give tremendous performances in their own right, notably DiCaprio in what could be his most challenging role to date—consider the fact that he had to not just act in Tarantino’s film, or play an actor working on the sets of other directors’ productions, but to also act in each of those films.

As much as Hollywood revolves around the professional exploits of Rick and Cliff, the seeming periphery of Sharon Tate’s story and the cult family of Charles Manson would grow in importance through the course of the movie. How Tarantino weaves everything together is screenwriting magic at the highest order, giving history and imagination an equal stake in the proceedings. As a result, QT’s work here is a bittersweet and remarkably sensitive take on the events of 1969. One might even see it as a time travel science-fiction movie, which to be frank, renders that bothersome Bruce Lee controversy utterly moot.