While there has been continuous debate over whether 1917 truly is a great film, or an overrated, pretentious technical gimmick instead, there is usually some kind of consensus—that it is a tremendous feat of filmmaking. Putting that debate aside, this article focuses on several feats, or ‘magic tricks’ that director Sam Mendes and cinematographer Roger Deakins successfully attempted to achieve their vision for the movie.

The Illusion of the One-Shot

Making a film look as if it was filmed in one single, uninterrupted shot (or ‘one-shot’) has occupied many filmmakers for decades. 1917 is, of course, not the first of its kind. Alfred Hitchcock famously did it with Rope in 1948, while more recent examples include Birdman (2014), and some segments of Children of Men (2006) and Gravity (2013), which were accomplished by the same cinematographer, Emmanuel Lubezki.

In 1917, the technique used is similar, relying on both cinematographic (as captured or manipulated within the camera) and editing (manipulation in post-production), plus a great deal of choreographed ‘blocking’, where actors move within the movie set in a precise manner.

As such, this elaborate effort allows the filmmakers to identify points in the shot where they could stop and continue later with a different take so that two or more shots can be ‘stitched’ together giving the illusion of a seamless and immersive one-shot.

The entire film is made up of these ‘stitches’; in fact, according to Mendes, the shortest shot was no more than 40 seconds, while the longest was over eight minutes. (It would be fun to try to locate these ‘stiches’ when you watch it the second time—don’t distract yourself on your first viewing!)

Purists will, however, assert that this is a ‘cheat code’ way of filming a one-shot. For the real deal, go dig out films like Russian Ark (2002) or Victoria (2015), which literally go the distance without any breaks or ‘cuts’ in cinema’s favourite endurance test.

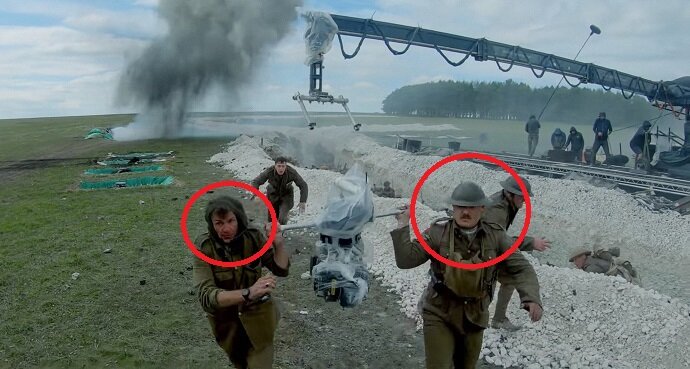

Director Sam Mendes (R) and cinematographer Roger Deakins (L)

The Magic of Light and Shadow

Roger Deakins is no stranger to lighting up some of the most memorable sequences in contemporary cinema. Think of James Bond’s silhouette fight scene up in the building in Skyfall (2012), also directed by Mendes; or the Zen-like safe haven of Niander Wallace (the villain as played by Jared Leto) in Blade Runner 2049 (2017).

In 1917, he took it to another level, particularly in the extraordinary burning church sequence, where the darkest of night was lit up by flares that were suspended on wires so that the shadows they produced were cast at different angles and speeds on the architectural ruins, as if they were ghoul-like figures terrorising and confusing the main character who is chased by an armed enemy soldier.

Moreover, the effect of the burning church, which is one of the physical hallmarks of the sequence, was accomplished by a lighting rig that contained more than 2,000 tungsten lamps that were positioned five stories high. With manipulation in post-production, the fiery effect of a lit church was spectacularly produced.

Space Is Time in Trench Warfare

An important part of filmmaking is its production design, where art directors and set designers work together to build convincing sets so that shooting can be maximised and controlled, as well as achieving a realistic look that the director wants. As 1917 is a movie set in WWI, where trenches were a defining physical characteristic, building trenches was a necessity.

But because of the illusive one-shot style of filmmaking employed, it was impossible to work with a restricted set that did not cater to flexible movement within the shot’s durée (or the duration of choreographed shot). As such, a more complex set was required to achieve the director’s vision.

The crew had to dig nearly a mile long of trenches, but more crucially, these trenches had to be able to accommodate the actors and numerous other extras, and designed in a way to allow creative and flexible use of the camera that avoided obstacles and followed the actors’ choreographed movements and pauses with absolute precision, and for an extended period of time. In other words, the relationship between space and time has never been more important than in the process of making this film.

The Camouflaged Crew

With such an ambitious picture filmed in long takes with hundreds of extras and elaborate camera movements, it is easy to make the schoolboy’s error of a camera operator or crew member running into the shot (imagine this happens in the last 10 seconds of a 8-minute long take!)

As such, in many of the complex sequences designed, the crew members were camouflaged as WWI soldiers, decked in their combat fatigues so that they could move freely within the shot in front of the camera.

For instance, they could be assisting other crew moving in parallel behind the camera by carrying equipment (also camouflaged), or to mount the camera on cranes or vehicles while the shot continued, in order to achieve cinematographic seamlessness and capture the scene in a variety of shot angles, sizes and pacing e.g. close-ups, aerial shots, speedier tracking shots, etc., where ‘stitching’ in post-production was not feasible.

In fact, some of these crew members who did double duty were paid extra as extras!